Free Resources to Teach Making Inferences

This blog post contains my Making Inferences eBook + Mini Unit. All of the information found in this blog post can be downloaded in my free printer-friendly Ebook found HERE .

Inferring is such an important part of reading comprehension. Unfortunately, it’s also a skill that confuses many students every year. It requires students to understand something about a text that an author didn’t come out and explicitly say. This requires students to flex some of their critical-thinking muscles.

If making inferences is giving your students trouble, I’m here to share some helpful tips and materials to guide students to mastery.

All of the printables used in this blog post can be accessed for free HERE in this Ebook.

The Importance of Inferring

Teaching inference skills is extremely important for our students. So much of readers’ understanding of the text is being able to fill in the gaps with their background knowledge. If students can’t think critically about what they’ve read, and read between the lines, a lot of the story will go over their head.

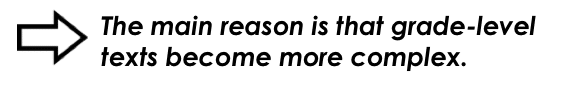

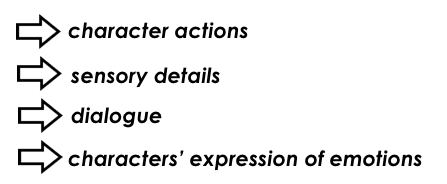

As students enter upper elementary, inferring becomes a skill that is absolutely essential for reading comprehension.

Increasingly, students will read books that require them to visualize, infer, and draw their own conclusions from the words of the text. Your students will find that authors no longer explicitly state all the details of an event or attributes about characters, for example. Instead, they reveal these details of the story through:

How Do I Teach Making Inferences?

Whenever I teach a new skill, I never jump right into texts. Scaffolding any lesson is really important, but it’s particularly helpful with inferring. I chunk my lesson using the steps below. Feel free to modify or differentiate for your learners as needed.

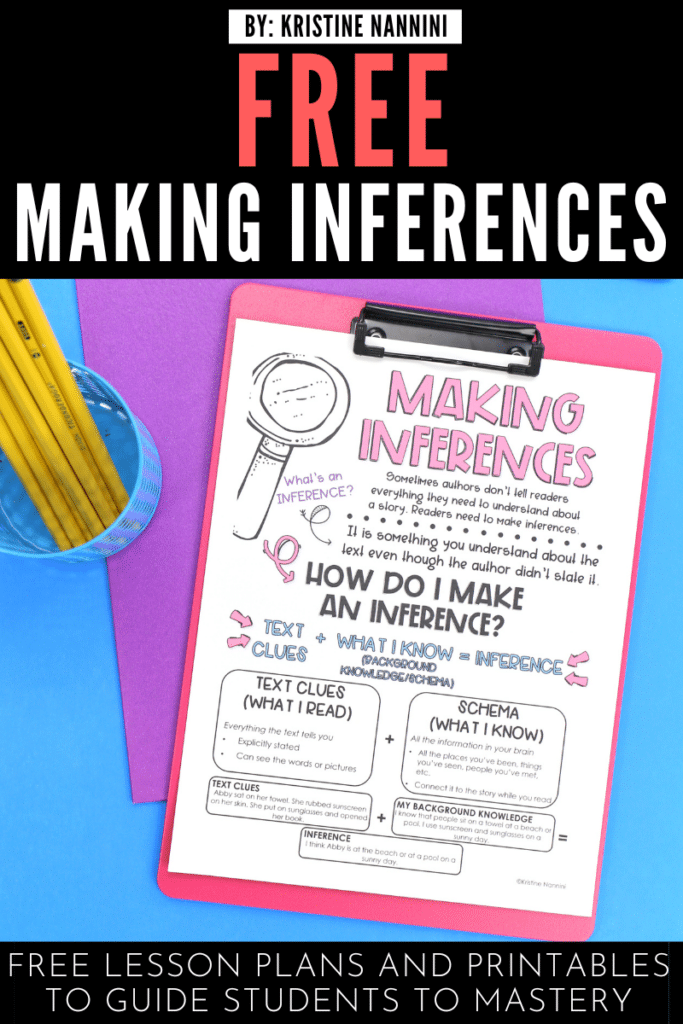

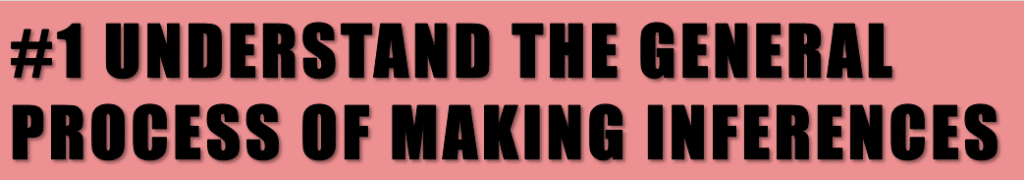

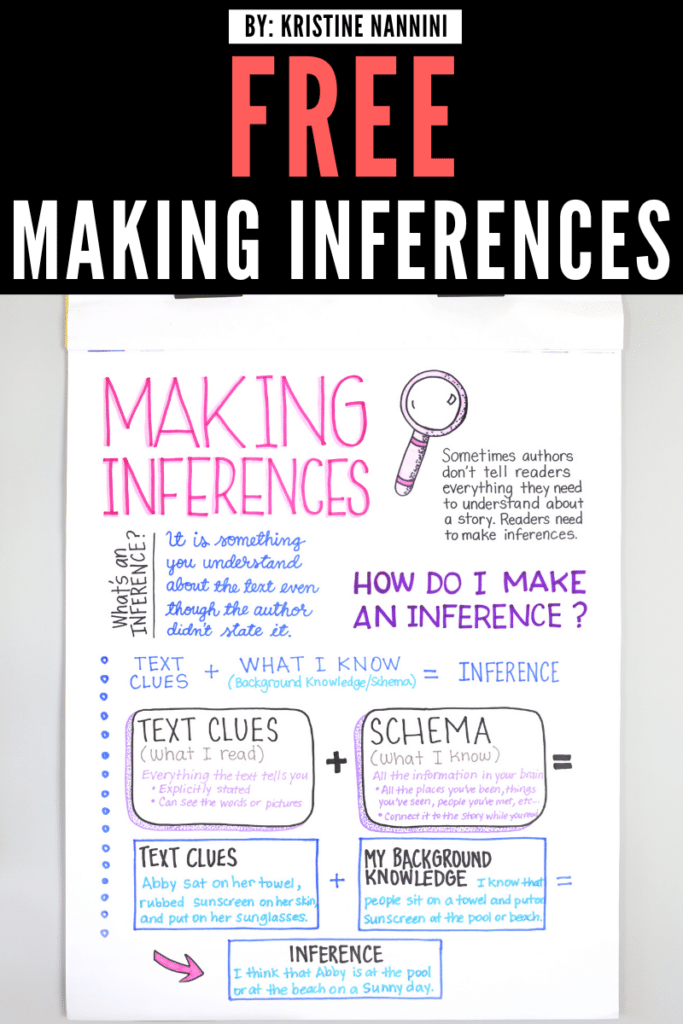

Due to the fact that we have a range of learners in our classroom, there will be students in your classroom who don’t know what an inference is. I start by defining the concept. An anchor chart is a great way to do that.

Use this as a model for making one with your students. In addition, you can find a printable version of this anchor chart HERE. Print this, and pass it out to students to keep or hang it in your room as a reference.

Creating an Anchor Chart with Students

Say to students:

- Sometimes, authors don’t tell readers everything they need to understand about a story. When this happens, readers need to make inferences. An inference is a guess that you can make based on what you read in the story. So how do you make these inferences or guesses?

- To make an inference, you read the text clues then you apply your own background knowledge (also known as schema) to those text clues to figure out what the author is saying.

- When you read a story, the author may not directly tell you that a character is happy. Instead the author might write that the character is “skipping along with a big smile on her face” as a clue. From your experience, or background knowledge, you know that if someone is skipping along with a big smile on their face, that usually means they are happy.

Some years, I went right into examples of inferences using pictures or short sentences. However, my students really benefitted from learning about schema first. They need the foundational tools to truly understand the step-by-step process of how to make an inference.

Teaching Schema to Students

Say to students: Schema is one very important part of inferring. Schema is your background knowledge based on all of the experiences you’ve had in your life. It’s basically like file folders in your brain that store everything you have ever learned or seen. Everyone’s schema is different based on their life experiences.

At this point in the lesson, I ask students, What does a house look like? Explain what a house looks like.

Say to students: You can explain it, because you have seen a house. However, everyone here probably has a different mental image of what a house looks like. But, because we’ve seen a house, lived in a house, or been in a house. A house is a part of our schema.

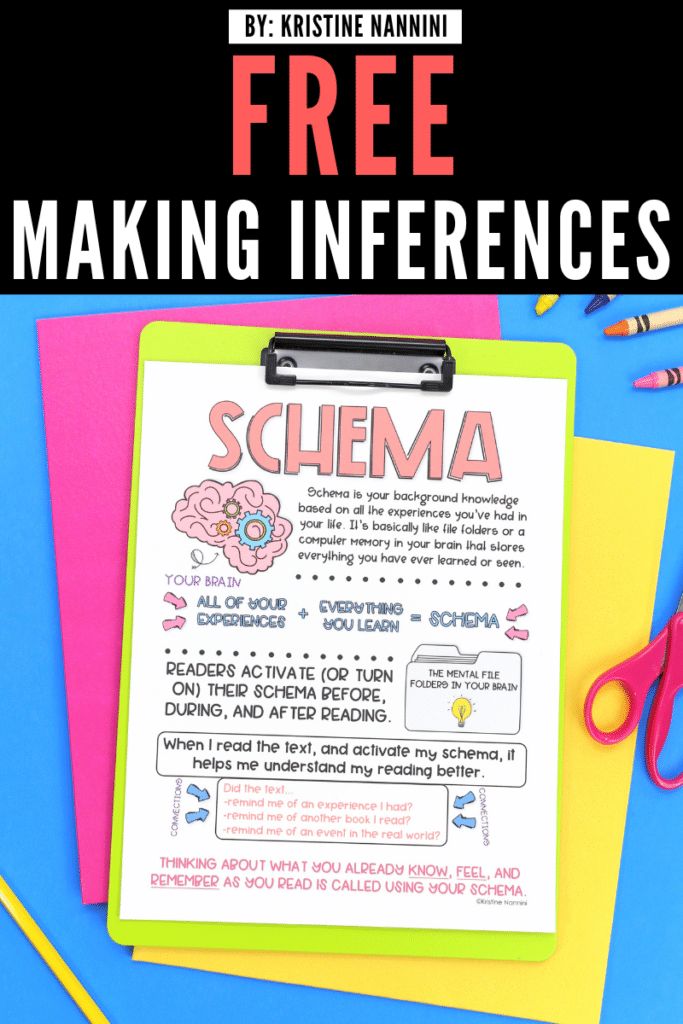

At this point, create an anchor chart on schema with your students.

I show an example of a completed anchor chart below. Use this as a model for making one with your students. In addition, you can find a printable version of this anchor chart HERE. Print this out and pass it out to students to keep or hang it in your room as a reference.

After making the anchor chart, lead a discussion with your students.

Have a Discussion About Schema

Say to students:

Tell me…

- everything know about places (beaches, jungles, forests, lakes, oceans)

- what you’d see at places (schools, parking lots, grocery stores, restaurants etc.)

- everything you know about things (vehicles, foods, toys, household items)

- what you know about people (doctors, teachers, friends, family, neighbors)

- all that you know about seasons/climates (winter, holidays, tropical, arctic, etc.)

Say to students: Schema is your background knowledge. Everything you know that is in your brain is a part of your schema. When you read, you apply your schema in order to understand what you are reading.

Use this opportunity to practice some examples of schema out loud with your students. See an example below.

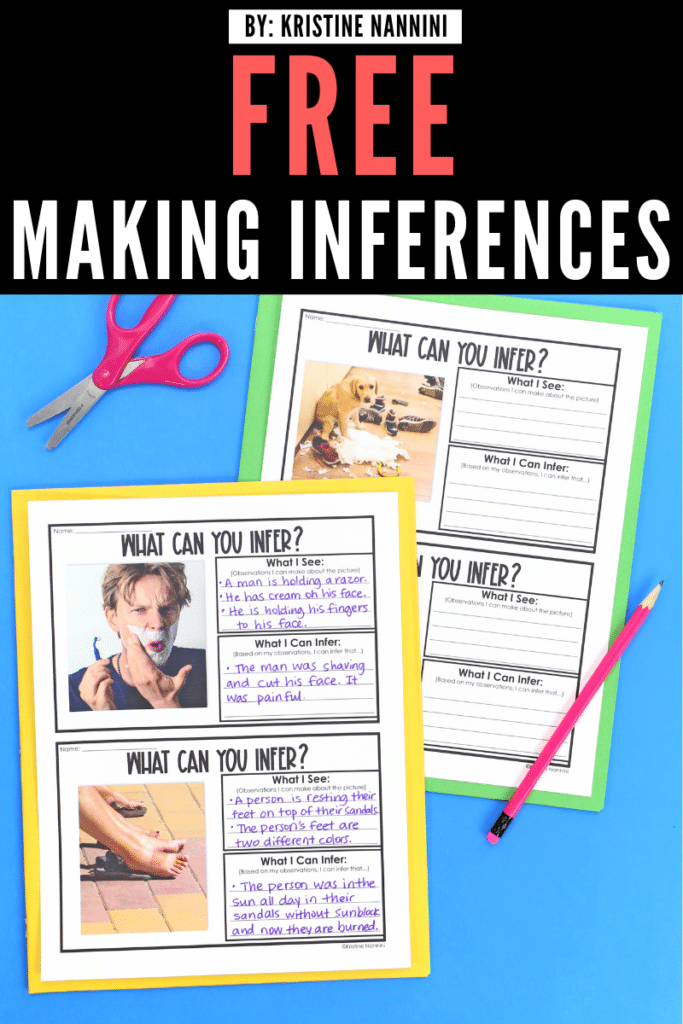

Making Inferences: Photos

Photos are a great starting point for students to make inferences on their own. A photo is a single narrow moment. All the clues that students need to focus on are easy to find and understand. With photos, you’ll see students focus on inferring, making guesses, and using the critical-thinking part of their brain.

You may want to begin by doing one with your students. Project a photo onto your screen. After showing students a photo, ask students:

How to Infer with Photos

Say to students: What do you see or what can you observe?

Make a list of everything that is actually there in the photo. You may have some students who jump right into inferring. Make sure you clearly discuss the difference between explicit observations and implicit inferences at this point.

After students brainstorm observations…

Say to students: Based on the observations we made, think about your schema or background knowledge. What do you think is going on in this photo? Or what do you think is happening?”

When students get the above correct, make sure you explicitly state that they looked at the clues in the picture, applied their schema or background knowledge and made an inference about what happened!

Other questions that can guide inferring or even help students further with inferencing skills:

- What is happening? or What happened?

- How is the person feeling in this picture?

- How do you know that?

- There aren’t any words in the picture to tell you that, what made you think that?

I absolutely love starting here with some of my lower readers. This is where I saw a lot of students finally “get it.” As a result, their confidence would soar.

What Am I? Riddle Guessing Game

What Am I? is a great game that you can incorporate into your lesson at any time. You can do this together as a whole class, you can split students up into small groups, or you can have students work with a partner. Guessing games are an easy way to help students continue their practice with making inferences.

What Am I? is a simple game where you describe something using clues, and students have to guess what it is based on the clues. To begin, I ask students to listen carefully as I provide clues. I stop after the sentence to see if any students would like to make an inference based on the clues I read with their schema or background knowledge. Again, make sure students understand that they are applying their schema or background knowledge to the clues to make an inference.

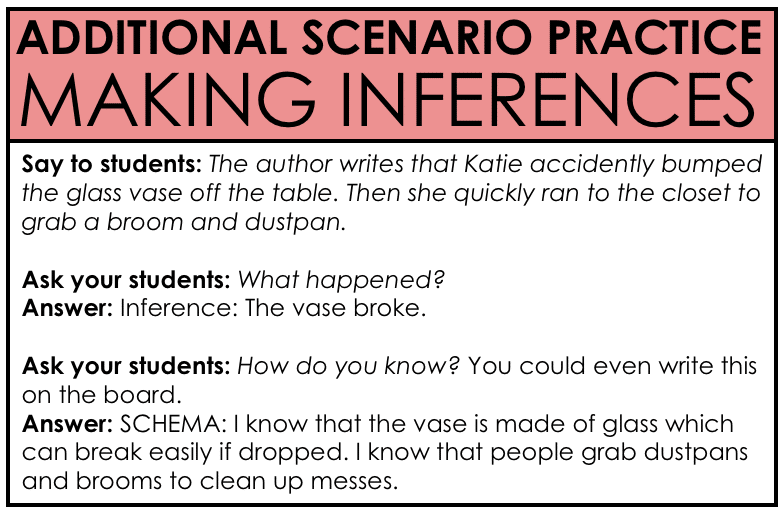

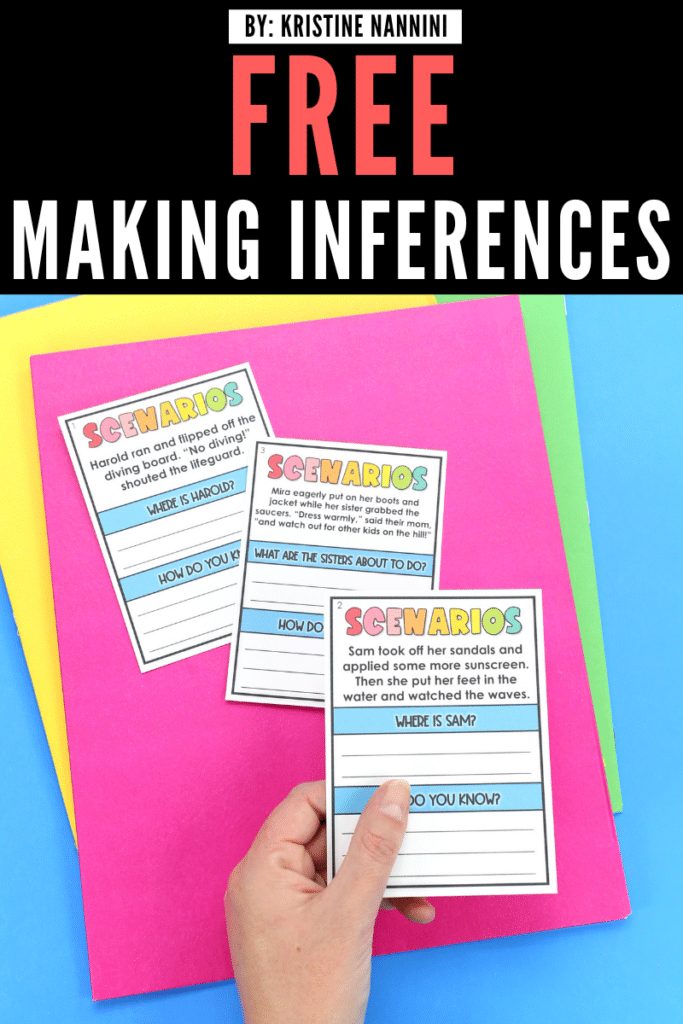

Incorporate Short Pieces of Text

A short scenario helps students focus on a few text clues in order to make an inference. There is one or two clues to focus on, and one very obvious inference students can make. If you had students infer with photos above, you may not have explicitly talked about the process of making an inference with a text. This would be a good time to reiterate the process when it comes to dealing with a text.

Say to students: Now that you understand schema and background knowledge, let’s practice making some simple inferences. Point to “How Do I Make An Inference?” on the anchor chart. Here are the steps to make an inference: First, you look at the text clues. These are the words that the author wrote in the text. Then, you apply what you know or your background knowledge/schema to those text clues. For example, let’s say the author wrote that the character could smell smoke and hear sirens blaring. Think in your brain about these text clues. Have you ever heard sirens blaring before? Have you ever smelled smoke before? Based on everything you know, what could the author be telling you?

There are a few examples below to practice out loud with your students.

Once you’ve gone through these examples, send students off to work on their own or in small groups to practice making inferences with short scenarios. You can grab the scenario freebies HERE.

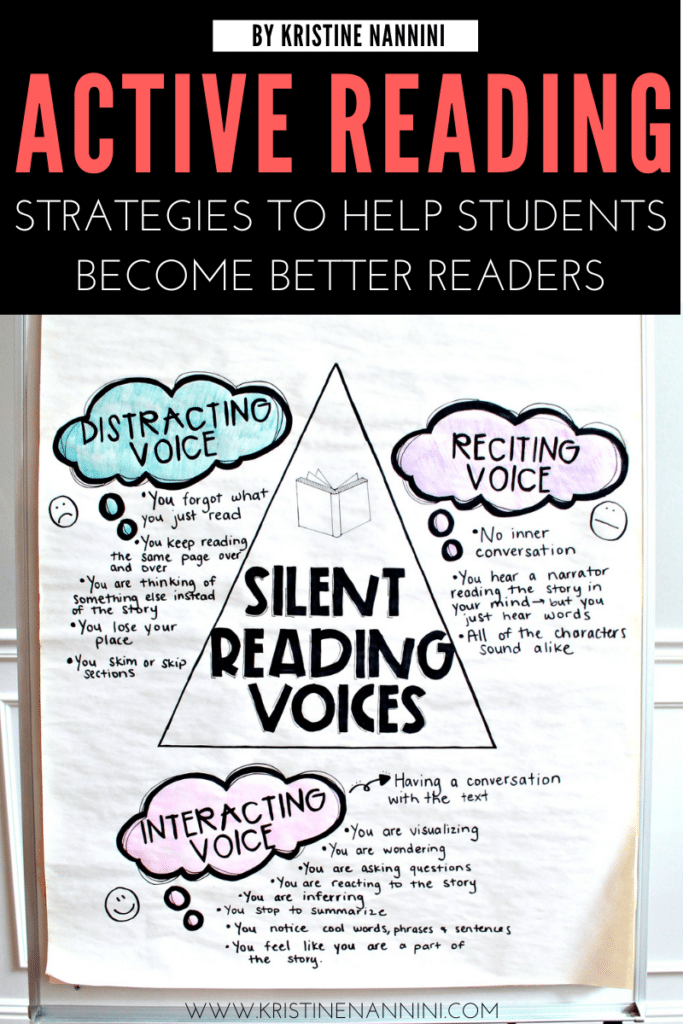

Teach Students to be Active Readers

There will be some students in your class who just read to take away a general understanding. They’ve never read a text to analyze it, make connections, or think deeply about it. In my opinion, this is the main reason why students struggle to infer. Inferring is such a high-level skill, and students truly need to understand how to interact with a text in order to master this skill.

Before I ever jumped into making inferences with a longer text, I explicitly taught how to interact with a text. Make this lesson quick. You don’t want to overwhelm students, but you do want to teach this. CLICK HERE TO READ THE BLOG POST.

Being an active reader is important when making inferences because it helps deepen understanding, uncover implicit meanings, and connect the dots between various pieces of information within a text. Here are a few reasons why active reading is important for making inferences:

Finding Hidden Information

Active readers ask questions and think about what the text doesn’t directly say. This helps us discover important details that are implied or hinted at in the text. Making inferences often depends on these hidden clues, and being an active reader helps us find them.

Paying Attention to Small Hints

Authors sometimes include small hints or clues that are easy to miss if we’re not paying attention. Active readers look closely at the words, tone, and context in the text to spot these subtle clues. These clues help us make inferences that go beyond what is explicitly stated.

Connecting information

Active readers look for connections between different parts of the text. We think about how the information fits together, and we use what we already know or have experienced to help us understand. By actively making these connections, we can make logical guesses and draw conclusions that go beyond what the text directly says.

Evaluating and revising inferences

Active readers are always thinking and reflecting on what they’re reading. We check if our ideas make sense and if there’s new information that might change our understanding. By actively questioning and thinking about our inferences, we can improve our understanding and make sure our guesses match what the text is telling us.

Thinking about the author’s purpose

Active readers think about why the author wrote the text and how they feel about it. We think about how the author’s purpose and point of view affect what they’re saying. By considering the author’s intentions and perspective, we can make better and more accurate inferences.

By actively engaging with the text, readers can unlock deeper layers of meaning and develop a more comprehensive understanding of the author’s message.

Say to students: When I read, there’s a lot going on in my brain. I’m thinking about the text, I’m stopping to summarize, I’m predicting what will happen next, I’m making a movie in my mind, I’m imagining what the characters look like, and I’m making inferences about what’s going on in the story.

READ MORE ON THE BLOG HERE.

Incorporate Longer Texts

Now that students have had the opportunity to practice making inferences with photos, a simple game, and simple scenarios, jump into a longer piece of text.

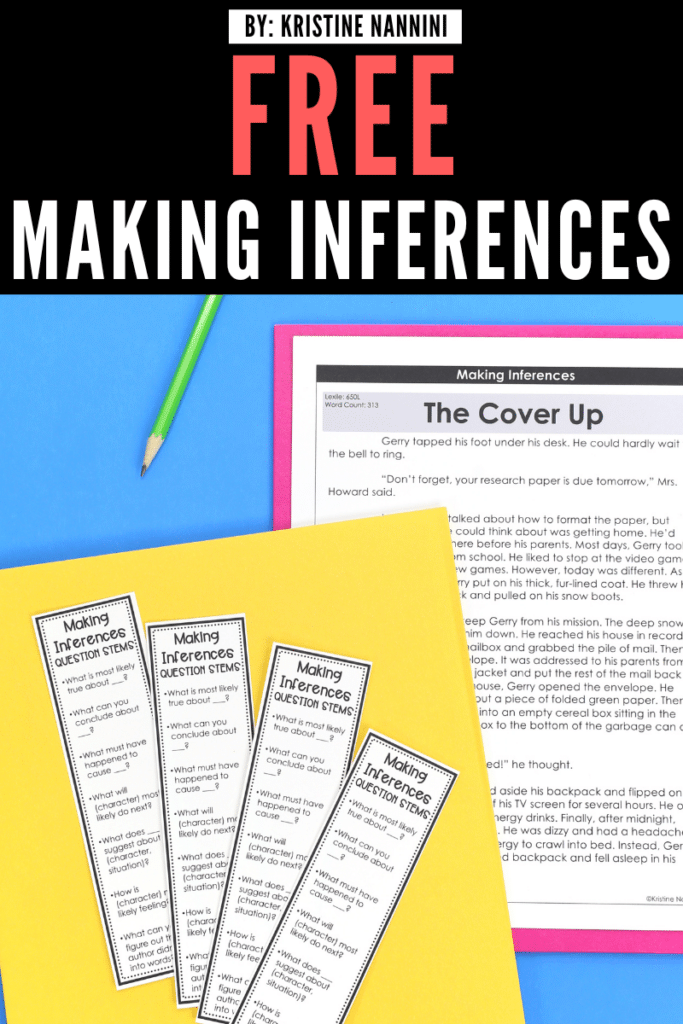

For the purpose of this lesson, I used the passage titled, “The Cover Up” from my Making Inferences resource found HERE. I wrote these passages specifically to help students build their inferring skills.

Use the printable (shown below) which you can find at the end of this resource to help guide your lesson. I note each place in the text where I infer, and I provide you with sample scripts for your lesson. Work with students at this step to talk them through the process of making an inferences.

Making Inferences: Independent Practice

Next, gradually release responsibility to your students. As they become more proficient, you should gradually decrease the level of support and allow students to take ownership of their learning.

Allow students to practice making inferences in their just-right self-selected texts or hand out leveled reading passages from one of my Making Inferences resources found HERE. Students can mark up their text with sticky notes, or you can hand out the bookmarks found at the end of this resource to encourage inferring.

After students get the opportunity to make inferences on their own, make sure you pull them to the carpet or just walk the room and call on students to share their inferences. In addition, use this opportunity to pull small groups to assess students’ level of understanding through an informal observation.

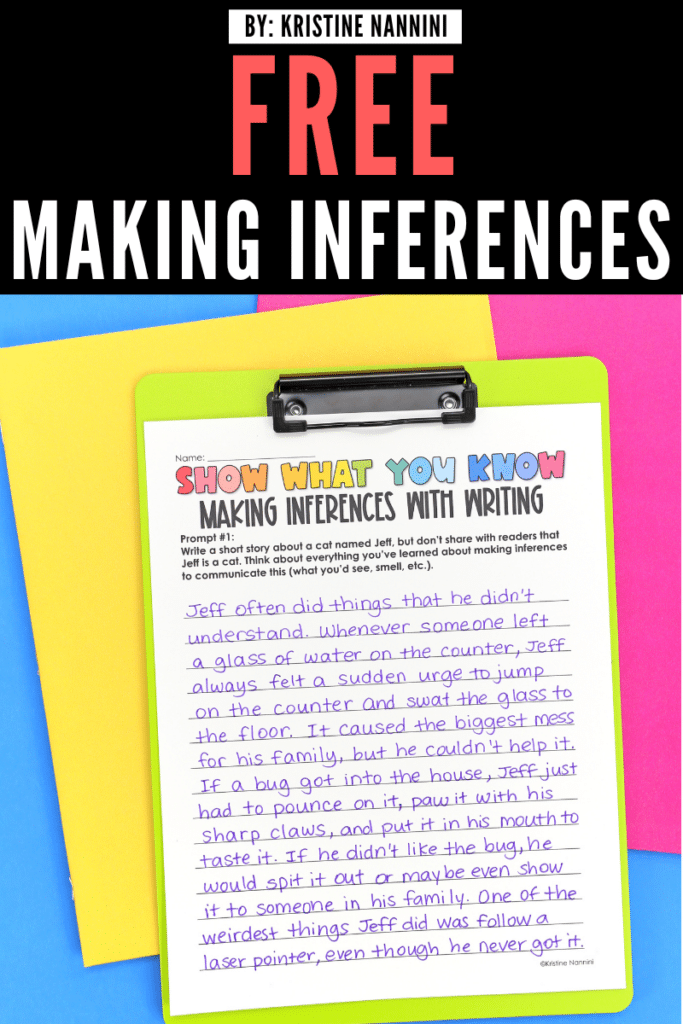

Making Inferences: Writing

Now that students have progressed through each learning activity to finally practice making inferences with a longer piece of text, you can extend their learning by allowing them to write their own examples of inferences. By doing this, students are synthesizing which allows for application of knowledge and can even serve as a form of assessment for teachers.

Having students synthesize and write their own examples of inferences is important for several reasons:

Reinforcement of learning

When students think of and write their own examples of inferences, it also helps them remember what they learned. By practicing and using their knowledge, they reinforce their understanding of how to make inferences.

Higher-order thinking skils

Synthesizing and writing their own examples of inferences require students to engage in higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, evaluation, and synthesis.

critical thinking abilities

They need to critically evaluate the information, identify relevant details, make connections, and then synthesize that information into an inference.

ownership of learning

When students create their own examples, they take ownership of their learning. By actively participating in the process, they become more engaged and invested in their understanding of inferences. This promotes a sense of ownership and empowers students to become active contributors to their learning experience.

application of knowledge

Synthesizing and writing their own examples of inferences allow students to apply their knowledge in a practical and meaningful way. It helps them understand how to figure out things that are not directly stated and how to make educated guesses based on clues.

Assessment of understanding

Assigning students to synthesize and write their own examples of inferences can serve as a form of assessment. It allows teachers to gauge students’ comprehension, application, and ability to articulate their understanding of inferences. Also, it provides valuable insights into individual student progress and helps identify areas that may need further support or instruction.

For English-learners, readers of different ability levels, or students needing additional support, consider the following strategies:

varied texts

Provide a range of texts at different reading levels or complexity to cater to the diverse abilities in your classroom.

graphic organizers

Implement graphic organizers such as concept maps, flowcharts, or Venn diagrams to visually represent the process of making inferences.

pre-teaching vocabulary

Introduce and explain key vocabulary words related to making inferences before starting the lesson.

multimodal resources

Provide a variety of resources such as videos, images, real-life examples, or audio recordings that present information related to making inferences.

individualized support

Provide one-on-one or small-group support for students who require additional assistance or have specific learning needs.

READ MORE ABOUT RE-TEACHING ON THE BLOG HERE.

Make sure you opt-in below to grab the free Making Inferences Ebook + Mini Unit.